Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Unlikely Companions in the NPG’s Latest Exhibition

- Megan Stevenson

- Apr 2, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: May 28, 2024

Portraits to Dream in brings prodigious artist Francesca Woodman and Victorian portraiture giant Julia Margaret Cameron, who worked a century apart, into a ‘dream space’ for us to revel in.

Untitled by Francesca Woodman (1979) and The Dream by Julia Margaret Cameron (1869)

Two photographs conjuring dreamlike states draw visitors into a dark blue entrance reminiscent of twilight. The first, by Woodman, shows a woman possibly sleeping, face cast in shadow, hands grasping at the sheets, caught in a dream. The second, The Dream by Cameron, shows model Mary Hillier posed in contemplation, a posy of flowers held to her chest. The stage is set; we expect ethereal, dream-like photographs to follow.

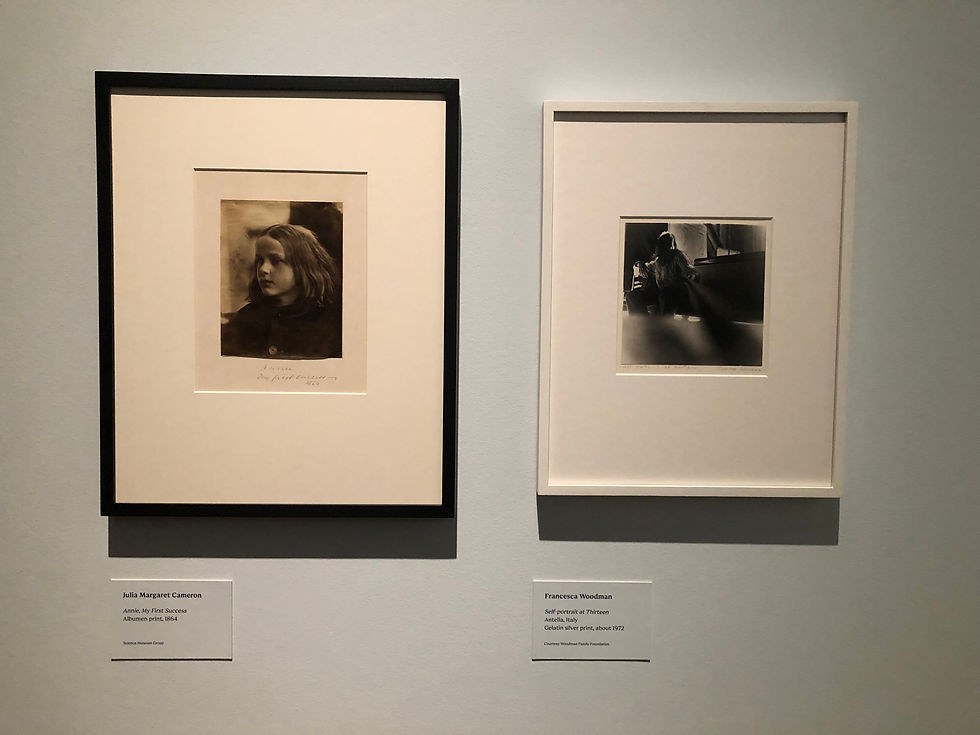

Annie, My First Success by Julia Margaret Cameron (1864) and Self-portrait at Thirteen by Francesca Woodman (c.1972)

The next space begins with two startlingly different images representing the early stages of Woodman and Cameron’s artistic journeys, Self-portrait at Thirteen by Woodman, and Annie, My First Success by Cameron. It was here that questions began to ring in my mind. Why are these two women being displayed together? These two early images are wildly different in form, references, purpose, and storytelling. What do we gain from this pairing?

Cameron, one of the best known portraitists of the 19th century, began taking photographs at the age of 48 after being gifted a camera. Woodman, on the other hand, produced her work throughout her teen years and early twenties, until her death at the age of 22 in 1981. She spent her youth between the US and Italy, where her family had a home, and her work was heavily inspired both by her Italian surroundings and a love of Victorian aesthetics.

There are some visual links to be made between Woodman and Cameron’s work in this exhibition. Both photographers constructed scenes, drawing on props and setting to produce fantastical images with the potential for many meanings to be brought forth. Both developed close relationships with specific models and muses who recur throughout their work. Both specifically referenced angels in multiple photographs. Yet further shared references are rare and there is no evidence that Woodman considered Cameron’s work when creating her own. The differences between the women, working in such different times (both in their own life stages, and in historical period) can at points in the exhibition seem too great of a chasm to leap.

In the Mythology section, Cameron’s staging of figures from myths and legends glow with the heavy meaning of stories Cameron wishes to tell. These character driven scenes are jarring against Woodman’s portraits, selected for their echoes of similar props or sentiment. Woodman’s much smaller works Easter Lillies and White Socks are reduced by their forced companionship with Cameron’s grand work representing Elaine of Astolat posed with Lancelot’s shield. Woodman’s surrealist tendencies, requiring space to consider and closely examine, aren’t given the necessary room to sing. It is at points such as this that the artists’ differences confuse, rather than heightening one another’s work.

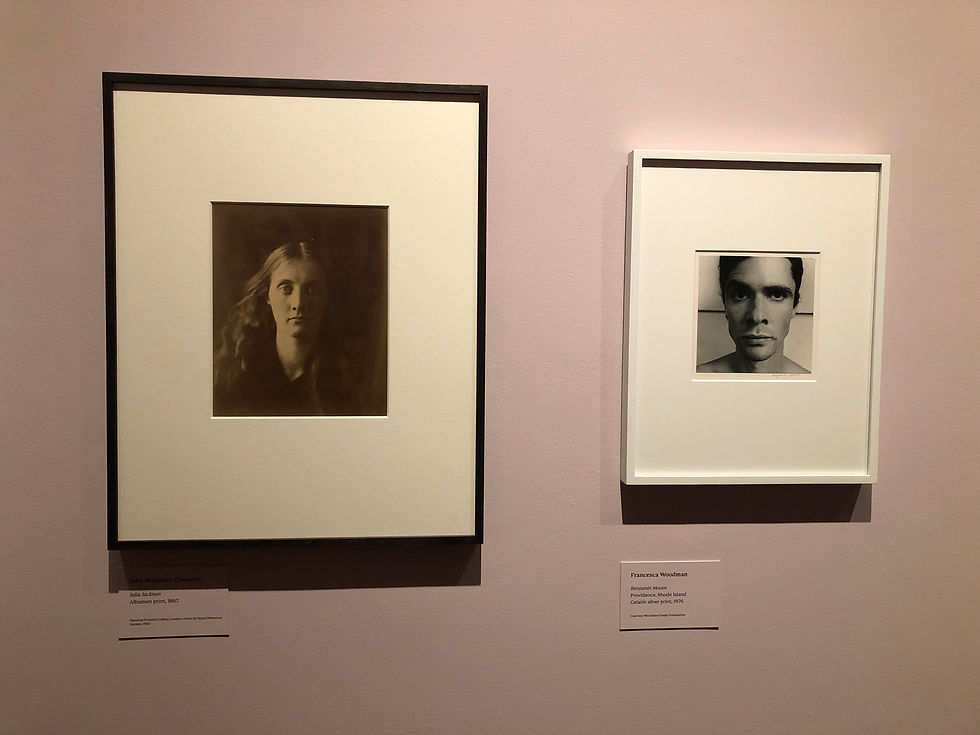

Julia Jackson by Julia Margaret Cameron (1867) and Benjamin Moore by Francesca Woodman (1976)

However, some portraits really do seem to spark off one another. The side-by-side hanging of Cameron’s Julia Jackson and Woodman’s Benjamin Moore is arresting. A century is traversed in the inches between the photos and we are confronted by two faces, impassively regarding our passing through their shared space.

To return to my earlier question, what do we gain from the pairing of these two photographers? An early text panel reads ‘This exhibition includes only original prints made by Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron in their lifetimes.’ To me, it is the nature of the prints that truly connects them, not their wider context. Yes, this exhibition is full of the ethereal images I hoped to find, but it is the artists’ relationship to their prints that connects them so intriguingly.

It is when we consider these photographs as objects, each printed by the artist and considered as a physical presence, not only an image, that this exhibition shines. The first of Cameron’s images on display quietly asserts this point. The Dream contains in its bottom right corner the unmistakeable fingerprint smudges of Cameron at work developing her photograph.

In the curator's talk held on Friday 22nd March at the NPG, curator Magdalene Keaney outlined the haptic nature of the prints on display. Indeed, the scrawls in corners, quotes written beneath images, torn edges, light leaks, and other physical attributes of the images are present across many of both Cameron and Woodman’s prints. Woodman went as far as to scribble over one untitled caryatid print, pasting it onto a page and sketching over the top. She embedded other prints into used notebooks found in Italy, covering the notations of past owners with her images, fusing photograph and object. Scale also plays an important role. Most of Woodman’s prints are smaller, introspective, looking at them creates the feeling of peering into her world. By contrast, her caryatids, the high point of the exhibition, stand tall and domineering in their space. Like Greek temple sculptures, they are larger than life structures, conjuring feelings of wonder and awe.

Cameron regularly made ‘mistakes’ in the developing process, yet printed and mounted the images regardless of contemporary critique of such practises. She also intentionally played with the development of her images, using light to create movement and auras around her sitters. Her approach to photography was in many ways scorned by her contemporaries, but when viewed alongside Woodman, we can see in her ghostly images a hand that plays with photography’s unpredictable nature, that revels in the ways light can be pulled across images, and that sees the photo as a print with fragile borders which can be altered and distorted.

This exhibition has brilliant photographs on display by both Woodman and Cameron. Although some sections feel disjointed in their pairings, the National Portrait Gallery has created space for a conversation to take place between Woodman and Cameron’s photographs. Between these two women we see the practise of image making being experimented with to produce many dream-like scenes, and, even if a little confusing, it’s a dream I would happily step into again.

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream in is on display at the National Portrait Gallery from 21 March - 16 June 2024, with accompanying catalogue by Magdalene Keaney available to purchase from the National Portrait Gallery shop.

Comments